SUZANNE O'CALLAGHAN

Suzanne O'Callaghan is HFA Policy Research and Education Manager

Over the last several years bleeding disorders in women and girls, treatment and care and improving quality of life have taken a front seat in international forums.

There was an impressive panel of key international experts speaking at the WFH Women & Girls Summit. Rather than delving deeply into recent research, they had been invited to give an overview of the current state of play with clinical practice and research and to lay the ground for future directions – although they did refer to some recent research studies to explain why practice is changing. At the beginning of each session a woman told her personal story of growing up and living with a bleeding disorder. I found these stories compelling. They gave a real sense of the lived experience to the presentations that followed, which often dealt with research tools and data and could be a bit distanced from the human aspects, and I thought were a great way to keep the focus on what is important.

How bleeding disorders affect QoL of women and girls with bleeding disorders

Chair: Prof Barbara Konkle, USA

Physician perspective – Prof Anjali Pawar, USA

Psychosocial perspective – Dr Sylvia von Mackensen

Quality of life in girls and women with bleeding disorders has attracted increased interest internationally in recent years. This session focussed on three aspects:

Manon Degenaar-Dujardin from the Netherlands began the session with her personal story, outlining her experiences of growing up and living with a severe bleeding disorder. She talked of the impact of her bleeding issues, having inherited both a Type 2 and a Type 3 VWD mutation from her parents. She was misdiagnosed with haemophilia as a child and grew up with all the bleeds of a severe bleeding disorder, but only blood transfusions for treatment. As an adolescent the bleeding with her first period was very severe. She was hospitalised and re-diagnosed with VWD rather than haemophilia, but accessing appropriate treatment remained a problem.

As a teenager she didn’t speak of her bleeding disorder to anyone other than her sister and felt very isolated. This made managing her periods harder – she spent a lot of time in the toilets and feared people would wonder whether she was trying to escape her schoolwork. It wasn’t until she went to university in Amsterdam and connected with the local haemophilia society that she learned about the local Haemophilia Treatment Centre and was able to access effective treatment. She talked of the difficulties she experienced in being believed – the common belief that only males have bleeding disorders and that VWD is only ever a mild bleeding disorder.

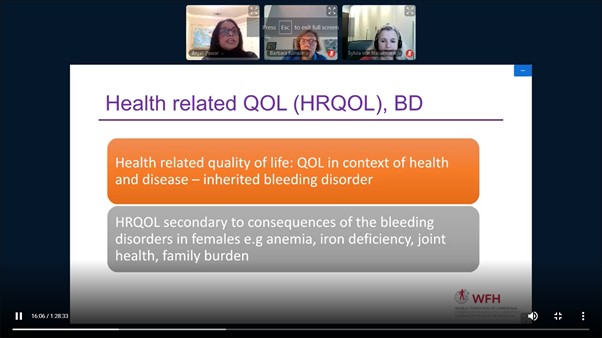

From the medical perspective, quality of life is a key element of care. Anjali Pawar explained that health-related quality of life involves:

Because they menstruate and can become pregnant and undergo childbirth, females have a different experience of a bleeding disorder to males. Their health-related quality of life reflects this, with issues around anaemia and iron deficiency, as well as joint health and family burden. To understand the outcomes of therapies for females, data needs to be collected on these consequences.

What kinds of measures are useful for girls and women with bleeding disorders? There is a range of standard questionnaires internationally. However, in bleeding disorders there are other significant questions. Pawar asked the audience to rate their own experience: fatigue, psychological issues, missing school or work, participating in sport, sexual life, medical coverage, feeling embarrassed, being bullied, knowing where to find information.

She noted a few issues that have been identified for adolescent girls:

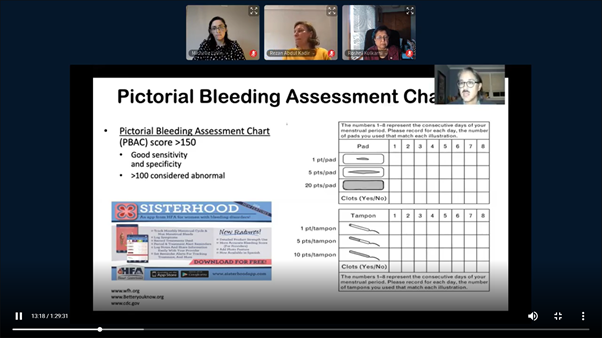

Regular use of high-quality assessment tools for menstrual bleeding, such as pictorial charts, will help to understand the impact of menstrual bleeding on these young women. She also described the results of studies about the impact of heavy menstrual bleeding on the decision-making of women with bleeding disorders.

Sylvia von Mackensen looked more closely at the psychological issues underlying health-related quality of life and the studies undertaken to measure it in women and girls with bleeding disorders.

She highlighted the areas where women with bleeding disorders can experience a lack of support – from their family, the health care system and the workplace. This can lead to women feeling impaired and isolated from others.

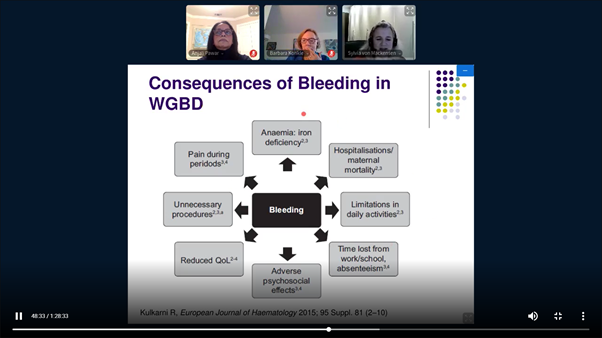

Heavy menstrual bleeding, sometimes called menorrhagia, is a common symptom of bleeding disorders in females. It has a wide impact on their life – on their bleeding, pain, ability to participate at work/school and at home, in sport and on their social interaction. Embarrassment and taboos about menstrual bleeding mean that women often do not speak about these problems or seek medical help for them.

Girls and women with severe bleeding disorders showed a lower quality of life than those with mild conditions.

Both Anjali Pawar and Sylvia von Mackensen identified a range of areas where quality of life is reduced for women and girls with bleeding disorders. They noted that the challenge ahead of us is to use this information to improve their quality of life. Can it be incorporated into research about the outcomes of treatment? What are other ways to make improvements?

Diagnosis & management of women and girls with bleeding disorders – Access to care

Hematologist perspectives:

Chair: Rezan Abdul Kadir, United Kingdom

How to diagnose a woman/girl and the challenges of making that diagnosis – Assoc Prof Robert Sidonio, USA

Management of women and girls with bleeding disorders – Dr Michelle Lavin, Ireland

Access to care and outreach – Prof Roshni Kulkarni, USA

Sharri Brodie, an Australian community member from Perth, started the session with a lively and honest account of her personal experiences. Sharri has mild haemophilia and von Willebrand disease (VWD). She didn’t know anything about bleeding disorders until her son was diagnosed with severe haemophilia at 5 years old. After a distressing period dealing with her son’s diagnosis, she eventually came to check her own factor levels and was diagnosed as a ‘symptomatic carrier’ herself. Looking back over her life, her many bleeding issues started to made sense – bruising easily, the black eyes, the heavy periods that she hated, the haemorrhaging with her wisdom teeth. Sharri described her guilt – about her son, for passing on the gene to him, and towards her husband, and wondered if he might have regretted marrying a ‘woman with these dodgy genes’. In spite of her fears, her son has never blamed her for his condition.

What has she learned from her experiences? Sharri spoke about the importance of knowing whether you carry the gene and support for family planning, which she has found very helpful. Until she had a hysterectomy in her 40s, her menstrual bleeding was controlled with the Mirena IUD (intra uterine device). She commented on the need for parents to educate their daughters about their bleeding disorder and how to manage their periods – and how, for example, to deal with judgemental responses about being on the contraceptive pill as treatment when it is usually associated with birth control. ‘Knowledge is power,’ she said.

Robert Sidonio outlined the tools that will help a physician to make a diagnosis of a bleeding disorder in a girl or woman.

BATs are bleeding assessment tools – such as the ISTH BAT and the Let’s Talk Period BAT. These help to make sure the range of questions are asked to identify the possibility of a bleeding disorder.

PBACs are Pictorial Bleeding Assessment Charts, which help to quantify how much a girl or woman is bleeding during her period.

Other useful assessment tools include the Menorrhagia-Specific Screening tool, which looks for any of these criteria:

Sidonio noted that using several assessment and screening tools together is much more likely to identify bleeding disorders in females, particularly adolescent girls.

Other important tools include:

Efforts to improve VWD diagnosis over the last 10 years have been paying off. Sidonio showed the increasing numbers of females with VWD being diagnosed and treated by HTCs in the USA and commented that this is an international trend.

He noted that there is still work to do in the future. Many females with VWD are being diagnosed as adults and it is important to identify them at a younger age. There also needs to be more research on females who carry the gene for haemophilia.

Michelle Lavin made a point of highlighting that although there are overarching principles of care, clinical management of women and girls with bleeding disorders is personalised to the bleeding issues and needs of the individual, and these can vary greatly.

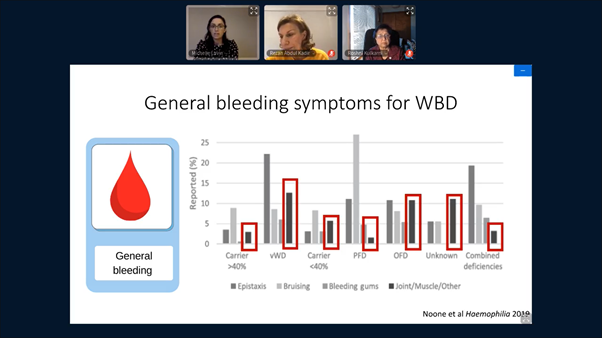

She outlined the results from a recent European Haemophilia Consortium survey of women. It had some surprising results – that women and girls often reported joint and muscle bleeds and general bleeding issues as well has heavy menstrual bleeding. Menstrual problems are the most common symptom of a bleeding disorder for females, both at the beginning of menstruation (the menarche) and at menopause. Women also need support during pregnancy, if they are using hormonal contraception as a treatment but need to stop taking it to conceive, and also at childbirth.

Menstrual bleeding may not be recognised as unusually heavy within a family if the women in that family all have heavy menstrual bleeding. This can lead to late diagnosis and management. Like Robert Sidonio, Lavin underlined the need to monitor menstrual bleeding objectively and mentioned a couple of apps as examples – Sisterhood and Flo Wellness & Period Tracker. There is a range of therapies available to help manage menstrual bleeding, include hormonal contraceptives if the woman is not trying to become pregnant. Iron deficiency and anaemia may also be problems and need to be treated proactively and carefully.

The HTC multidisciplinary team will need to provide support to a girl’s parents and a woman’s partner and family over their lifetime. Because HTCs have a family-centred care approach, it is important to use this as an opportunity to identify other people in the family who may also have the bleeding disorder.

Lavin finished her presentation noting that we are at an exciting time in bleeding disorders management, transitioning to a new paradigm of care for women and girls.

Roshni Kulkarni pointed out the need for an outreach approach for women with bleeding disorders: often they are very involved in looking after their family and services and find it difficult to access services. To increase access to services, there needs to be flexibility, including telemedicine, and to consider outreach as an option, particularly for girls and women who live at a considerable distance to the HTC.

Kulkarni described the approach to telemedicine in her paediatric HTC, where a family physician/GP can conduct the consultation in collaboration with the multidisciplinary team at the HTC. Conducting telemedicine with the patient at their home also enables the HTC team to see the home environment and how the patient moves around at home. Genetic counselling can also be undertaken via telemedicine.

Telemedicine has been particularly valuable during the COVID-19 epidemic. Kulkarni noted there were some practical challenges, including communication over poor connections and some patients’ lack of access to internet.

There was a clear message from the Summit that much work is still to be done. While treatment and care is personalised to the individual and their needs, we still need a better understanding of the impact of a bleeding disorder on the symptoms of girls and women. Michelle Lavin highlighted that the symptoms and issues of girls and women can vary greatly. It was helpful to hear that women and girls can use tools like Pictorial Bleeding Assessment Charts to give an objective view of their menstrual bleeding. However, data and research into general bleeding symptoms of females as well as menstrual bleeding will be important to support comprehensive care into the future.

Haemophilia Foundation Australia acknowledges the Traditional Owners and Custodians of Country throughout Australia, the land, waters and community where we walk, live, meet and work. We pay our respects to Elders past and present and extend that respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Sign up for the latest news, events and our free National Haemophilia magazine